Warning: there is adult content in this post.

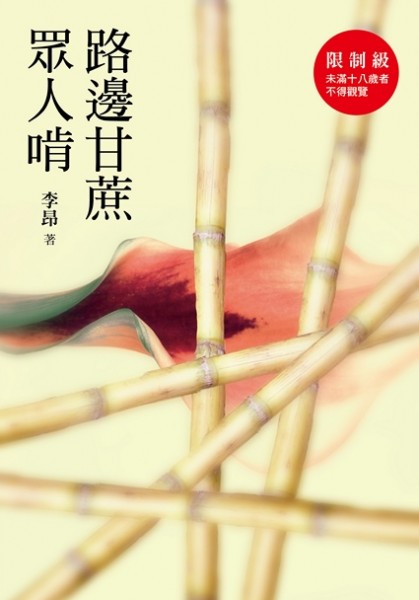

This is Li Ang’s much anticipated follow up to her 1997 book Everybody sticks it in the Beigang Incense Burner (《北港香爐人人插》), which I’ve yet to read. At first glance it is an irreverent look at the misogynistic self-aggrandizement that characterizes the generation of democracy campaigners who rose to fame after being imprisoned in the martial law era in Taiwan, some of whom later formed the Democratic Progressive Party and went into government under former president Chen Shui-bian. The book also deals with the symptomatic nature of the way the February 28 incident and the White Terror continue to manifest themselves in the political arena. Although this might seem a rather obscure or outdated theme, it can give us an insight into the background of the political mindset in today’s Taiwan, particularly in light of the recent Sunflower Movement and the problems in governance that it has highlighted. The attempt to smear the participants of the Sunflower Movement in March and April as violent rioters, for example, is reminiscent of the Kuomintang’s rhetoric against democracy protesters during the 1980s and 1990s that features in the book.

The book centres around the life of Chen Junying (陳俊英) from his youth as a dissident during the Martial Law era, to his slow drift into irrelevance as a retired politician living in the US in his later years. Li Ang goes to great pains in the introduction, stating several times that the character isn’t based on any one person in particular – her protestations are so frequent however that it’s almost as if she’s prompting us to take this denial with a pinch of salt.

Chen feels owed by Taiwanese society and Taiwanese women in particular and he has a mantra that recurs throughout the book which rationalizes his misogynistic behavior:

(My translation) He was forever the one being let down, it wasn’t just the Taiwanese people who owed him, didn’t Taiwanese women owe him too‽ So it was natural for him to sleep with a good number of women when he came out of jail.

The book can be read as a satire up to a point and parts of it are quite funny, recalling the satirical bite of Wang Chen-ho’s Rose, Rose, I Love You /《玫瑰玫瑰我愛你》, like the protagonist’s assumption that he will ejaculate more than other men because of the years he spent in prison, and because he thinks so much of his own masculinity:

(My Translation) She discovered that Chen Junying was excessively liberal with toilet paper after making love. When he climaxed, he didn’t leave that much ejaculate in her (his sperm wasn’t particularly greater in volume than other men, nor did it smell fishier), and not much of it would drip out of her vagina after they’d finished, so one or two sheets of toilet paper would have been enough to absorb it all. He would grab a handful of tissue from the box, however, and pass her a pile, watching her as she meticulously wiped herself clean of any trace until all of the tissue was used up.

In the same vein, Chen takes a very chauvinistic attitude during sex, as, despite being reviled as a dissident by many women in his youth, he still finds time to grumble about the only girl who is willing to get together with him, and treats her with scorn, viewing her status as the product of a “mixed marriage” between a mainland soldier and an aborigine as below his – with a lot of his fellow dissidents using the phrase 「無魚蝦也好」 (bô hî, hê mā ho – If there’s no fish, you can make do with shrimp) to tease him

about their relationship and Chen himself often emphasizes his disgust at not being the only man she’s ever had:

(My Translation) Lin Huishu didn’t know that when she opened her legs and Chen Junying was inside her exposed vagina, that he was plagued by the sensation that other penises were constantly moving in and out of her wet juices, fucking her, and that they had already given her great satisfaction. Watching her as he jerked violently at her senstive parts, blood rushing to her vagina as she spasmed with pleasure so that her back arched and her feet stretched out to their tips –

Compliant.

Chen Junying thought he was seeing the accumulated effect of all the different men’s cocks on her body:

This was a loose abo girl, with all the habits of of her abo ancestors, this is how she responded and enjoyed herself. Chen Junying felt it was an orgy. And the idea that Lin Huishu’s vagina was enjoying the after-effects of all those penises, thick ones, thin ones, long ones, short ones, soft ones, hard ones, of different temperatures, of different shapes, with different kinds of foreskin or with the foreskin removed to different extents, was constantly in his mind. (pg 33)

This becomes more amusing with another of Chen Junying’s women who, as a Taiwanese-American is totally unaware of his attempts to slut-shame her, and who takes it at face value:

(My Translation) “When you sucked American cock, I bet it was tasty and filled you up good!”

Ding Xin didn’t think there was anything untoward behind his question and answered truthfully, she even tried to show off her generation’s knowledge about sex, the forward-thinking young women they were:

“Yeah, I sucked them! That’s pretty standard!”

“Was it a a really big one?”

“It wasn’t small”

“He must have really fucked you good!”

“Yeah, it was really good, I guess I’m quite lucky, all the men I’ve met have been good in bed.” In a concerted effort to make the man on top of her feel better about himself she added: “Doesn’t everyone say that Western men are just big, but that Eastern men, especially Taiwanese men, are better in bed.”

There’s also a very amusing scene chronicling the first DPP presidential inauguration, in which local Taiwanese women wear Western style evening gowns under the heat of the Taiwanese sun and sit on plastic chairs, as they are unfamiliar with this kind of ceremony, but at the same time they are so jubilant that they don’t care about the how they look, although this joy in tainted with the author’s later disappointment with the party. This portrays quite vividly the perceived class differences that lie in the divide between the KMT and the DPP at their roots.

The book has a darker version of the comedy in Veep, The Thick of It and The Office in some parts, in a passage where Chen Junying attempts to please imaginary cameras on the MRT by buying flowers from a peddler with Down’s syndrome for example, while imagining the headlines or media coverage that it might bring him, though it doesn’t quite go to plan:

(My translation) As the MRT station was just about to close for the night, at around midnight there was a Down syndrome boy pushing a cart with a few single flowers weaving around, as he walked past he was a bit shocked that someone had let the kid come out alone to sell flowers so late at night.

He plucked out NT$100 without thinking and took a white rose from the cart.

He couldn’t tell his age by looking at him, he was probably in his early teens, with a face on which the pale features crowded towards the center, and the whites of his expressionless eyes turned to him for a second, before he pushed his cart onward.He strode forward, took another flower, one with nicely formed petals, and gave the boy another NT$100 note. After taking it the child turned around with the same lack of expression.

(At these kinds of moments, there would normally be a camera to film and normally in his prearranged ‘bits’, the child who took the money would have a grateful expression and, most important, he would remain standing in the same place, then he would ruffle up the child’s hair and bend over, or even squat down beside him and ask him in a pitying voice “What age are you, young man?” or say “You’re such a hard little worker!” If the child was small enough, he would pick them up, but he would have to make sure beforehand that the child wouldn’t cry and wasn’t overly shy.

Then he would stand up and talk to the camera about caring for the vulnerable in society.)

He didn’t know how many more $100 notes there were in his pocket, he thought the child would have known to give change, luckily he saw a reddish note still in there. The child was still in front of him, pulling the cart quite roughly, as he wasn’t too good at predicting its movements he kept bashing it off things, his body seemed disjointed, splashing about messily while walking forward, he looked to be in an awful hurry but wasn’t actually making much progress.

He gave the red bill in his hand to the child, and took another light coloured rose. The child took it without even looking at him, as if it didn’t matter what it was he was taking.

(Could there have been a camera filming? Even if there wasn’t a camera, it’s the internet era, maybe a passenger would recognize him, one of his supporters, maybe they’d take out their camera phone and film him, even if the footage would be a little grainy, it would look more natural.

When they uploaded it to the internet it might even go viral. His assistants were always telling him to focus on the internet more, if he’d done what they said maybe he would have amounted to more!

It hadn’t been so long since he’d stepped down, there must be someone who recognized him and someone would surely be filming‽)

Would someone be filming? The MRT was still bustling with people, had someone seen? He hadn’t arranged this ahead of time with the Down syndrome child, it had all occurred by chance. Was it the alcohol playing tricks on him? He felt like there were tears coming to his eyes, not real tears, they didn’t blur his vision or trickle down his face. He’d had dry eyes for so many years, he’d lost count.

(How long had it been since he’d cried?)

He felt like tears were coming however. He took out another red note that he’d seen in his wallet and picked out another flower, he noticed that it was a lily, a Taiwanese lily, a pure white trumpet-shaped flower with a light fragrance. On the protest site, they had appeared everywhere, especially on the anniversary of February 28th.

(Was it also chosen as Taiwan’s national flower? Was Taiwan’s national flower the lily or was it the azalea? He’d been at the flower designation ceremony, but he didn’t remember. His memory!)

It took him by surprise this time when the boy took the money, as though he didn’t show his teeth, it was clear that his mouth formed the words Thank you!

He was stunned for a moment, at the effort on his crooked, bunched up face to form drawn-out syllables as his mouth opened.

The book tries to counter the deification of those who took part in the democracy movement, and portrays them instead in a human light, puffed up with self-importance. I think the kind of rhetoric that Li Ang is poking holes into was also evident during the Sunflower Student Movement, a kind of saviour complex, or a feeling of being owed, like in these two separate posts taken from a friend’s Facebook account when he was occupying the Legislative Yuan in March:

別人我管不著,但是自己的朋友在這種時候那說政治冷感的話,我只會想打你巴掌到你雙頰熱感為止。

I can’t tell other people what to do, but whenever my friends tell me that they are cold (apathetic) on politics at a time like this, it makes me want to slap them around the face until both of their cheeks are hot.

如果我們不小心用血守護到你的未來,不客氣。

If we inadvertently protect your future too with our blood, you’re welcome.

I was reminded of these Facebook posts every time I saw Chen Junying’s mantra repeated throughout the novel. The cult around the leaders of pro-democracy veterans is also seen with the leaders of the Sunflower Movement today – angry rhetoric at the inaction of other Taiwanese people who are not of their point of view, or who are apathetic, has touches of rhetoric about being “owed” or making sacrifices for the Taiwanese people.

In this appearance from Lin Fei-fan, he gets teary-eyed and indignant at the idea that politics could involve… well… politics. His high-minded ideals suggest to us what Chen Junying and his fellow democracy advocates must have been like in their youth, but this novel perhaps gives us an insight into the possible risks that come from buying into this kind of holier-than-thou stance and how it ages.

The reader is shown how this kind of sacrifice becomes a badge of honor and is used for political gains and that suffering is held to imply moral superiority, with rivals striving to be named Taiwan’s Mandela:

(My translation) Being in prison for such a long time, although it won him the romantic title of being an opposition hero, Chen Junying wished that he could be like his fellow political prisoner, Lin Shuyang*, who had been in prison the longest and be praised as a “personality”; among the people in the party that he saw as rivals, there were many who had been in jail longer than him, and received all the praise, one of them was even called “Taiwan’s Mandela”.

*Leftist intellectual from a prominent local family who was jailed in 1950 for his leftist leanings and was freed in 1984. After he was freed he advocated for unification with China.

The sense of debt continues to feature throughout the book and forms of corruption by the new administration are excused as “compensation” for their sacrifices. This brings up the idea of transitional justice, and whether both sides can come together and let the past be the past. This was seen in the attitude of some members in the DPP when Chen Shui-bian’s corrupt dealings as president were revealed, with some commentators rationalizing it as only fair given the KMT’s history of corruption.

The contrast between satire and solemnity however, works to undercut any sense of preachiness in the book. The author gives a nod to a certain perspective on the scale of the violence in Taiwan compared with other countries, which is clear in the author’s prologue:

(My translation) Amid global trends, the Jasmine revolution began and has had a certain amount of success. In contrast, in Taiwan’s process of democratization there were never any coups, or bloody revolutions, the sacrifices made were less than elsewhere, and now more than a decade later democracy has taken root, and moved past the more tragic past. (pg 12)

A brief history of Taiwan is sketched out in these passages which are marked out in a different font, including the February 28th Incident, the White Terror, the Kaohsiung Incident and the pro-democracy movement, as well as the subsequent political rehabilitation of former dissidents.

The solemn voice merely informs us of the main events in Taiwan’s transition at first:

(My translation) After the Second World War, the Republic of China government assumed control of Taiwan, at first they were welcomed by the Taiwanese, who were full of hope and expectation, little did they know of the corrupt governance that would characterize the post-war era or of the economic monopoly. The people would gradually lose heart and later would voice their discontent.

On the evening of February 28th, 1947, Yanping North Road an inspector from the Monopolies Bureau injured a woman who was selling cigarettes on the street and ended up firing into the crowd and killing someone. After protests by the residents of Taipei for the authorities to address the issue went unanswered, citizens were instead fired upon with a machine gun by order of the office of the Chief Executive, things became more difficult to contain and swept the entire island – island-wide dissent.

The chairman of the National Government Chiang Kai-shek had words with a member of the Bureau of Investigation and Statistics under Chen Yi’s military government and had more troops sent to Taiwan.

At dusk on March 8th, the Nationalist Army made land in Keelung, and advanced southwards, suppressing and committing massacres as they went, the casualties were severe.

On March 20th, the chief executive launched an island-wide “clearing of the villages,” extending the slaughter to every corner of the island.

As the book progresses, however, the passages, set off from the rest of the book with a different font, start to break down into a more subjective personal account, adopting a more emotional dream-like narrative line recounting torture:

(My translation) Dragged into the back room, for a minute all that could be heard were the sounds of punches and kicks and people’s screams that were unbearable to hear, after fifteen minutes, carried back to the interrogation room, short of breath crouching over the desk, hair, eyes, nostrils and mouth soaked with blood gurgling out, body shaking violently.

An exhausting night of interrogation, a light shines strongly, drinking salt water, sitting naked on a block of ice, the tiger bench, anal penetration with lit wooden stakes, the airplane position, military medals piercing bare flesh, hands crushed by a rack, fingernails removed, needles piercing into the fleshy bits between fingers, water boarding, squatting on the toilet and electric shocks.

There was also the removal of teeth, squatting on wooden spikes, being forced to swallow water with chilies soaking in it, being forced to swallow gasoline, one’s arms being beaten while tied to a single bed, the ‘journey to hell’, wherein prisoners were locked in a pitch dark cave and forced to listen to recordings of other prisoners being tortured, insertion of toothbrushes into the vagina, burning the head of the penis, compelled masturbation, filling the nostrils with lime, being forced to eat dog feces and bursting the testicles. pg 236

For more information on these horrible torture techniques, check out these two blogs: English, Chinese (and this one).

The final image provided to us in the text of a different font is one of a woman being hung to make it look like a suicide. She is pregnant and miscarries. Despite the obvious signs that she has been forced into the act, the government pose it as her hanging herself out of guilt for her crimes. We can only assume that her pregnancy is the ‘crime’ in question, as there is no further context given. If this is a reference to a specific incident it’s beyond my limited knowledge and I’m also unaware if this was part of the White Terror, or just a result of patriarchal society’s attitude towards women. Regardless, it is significant in that throughout the novel men are seen as those who are acknowledged as sacrificing themselves for Taiwanese people, and therefore license is granted for them to be misogynistic. The only sincere examples of self-sacrifice in the narrative of the book, however, seem to be those from Lin Hui-shu, as we see her put her hand under Chen’s mosquito net to prevent him from being bitten by mosquitoes, so that they will bite her first.

There was a point in the book that made me uncomfortable and that is why I say it is satire up to a point. I think that Li Ang wanted to make the book more than a satire, and so she undermines the genre by introducing a stain on Chen’s character that puts him beyond the scope of the affectionate distaste we have for the characters in Wang Chen-ho’s Rose, Rose, I Love You. Chen is now old and finds it hard to get an erection, he is in an airport lounge when a very young girl starts to eat cherries and hands him the pips which are still warm from her mouth. This gives Chen the urge to masturbate and he flees through the airport to his hotel to relieve himself, associating the cherry with the clitoris of a past lover. The passage pushed the book beyond satire, so much so, that it left me completely puzzled as to whether I should read it as a hint at the dirty laundry of the author’s former lover (as one character in the book, “the female author” could be interpreted as having some link to Li Ang herself), or whether it should just be read as an attempt to shake the reader out of attempting to simplify the novel by reading it as pure satire.

There was also a Buddhist reference in the book, though I didn’t really know how it fit into the narrative, this almost came across as orientalism on the part of the author in an perverse way, but maybe there’s more to it that I’ve missed (share your opinion below). There’s also a reference to a story by Milan Kundera in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, that doesn’t really seem to have a coherent place in the narrative but is interesting enough taken alone.

Despite the general cynicism about politics in the book, there’s also interesting details about Taiwan’s political scene. This description of the Democratic Progressive Party for example, gives us an interesting opinion of the party and of politics in general:

(My translation) Nominal members of the Democratic Progressive Party

In the historical development of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), nominal party members (人頭黨員) have had a substantial role. Except for the party primaries in which all party members vote, they are the most important element in the DPP’s pyramid structure. As a demonstration of the party’s internal democracy, party representatives are chosen by party members, who then go on to elect the Central Executive Committee, who in turn go on to elect Central Standing Committee members and the chairperson.

Each party nomination and party appointment has to be voted on by party members, therefore, everyone seeking to make it within the party cultivates a following of nominal party members. “The cultivation of nominal party members is the ecology of the DPP. If you don’t have your own party members, you won’t be able to go anywhere within the party.”

As not many ordinary people want to join political parties, those who want to, can cultivate a following of nominal party members. So in the party elections, these nominal party members sell their vote to the highest bidder, and can be very influential. Many of the founding members of the party lost enthusiasm for the party, unknowingly giving these nominal party members more power.

For more explanation on how politics works in Taiwan, you should definitely check out the brilliant and incisive Frozen Garlic Blog which is incredibly detailed and at the same time gives you a good grasp of prevailing opinion, for the DPP structure and election rules specifically, this and this post are particularly good reference material.

There was little mention of the cross-strait relationship within the book, except for a brief mention of smelly bumpkins on a flight that bother the protagonist, in a very vivid way through the medium of smell. Chen says of the smell of the mainland Chinese men that “the sudden way the smell came had a rhythm to it, like a melody constantly circling through his head, ghoulish music passing through his brain endlessly” and this episode concludes with the statement:

To Chen Junying, this is what China was, a sense of not being able to breathe–

The only other references to China that stood out to me in the book were a brief reference to Mao Zedong having slept with two thousand woman and the story of Empress Lü and Concubine Qi:

(My Translation) Human Pig

Liu Bang, the founder of the Han dynasty, and his wife Empress Lü, overcame many difficulties to conquer and unite China in 200BC. After he became Emperor, Liu was fond of Concubine Qi who excelled at dance moves with raised sleeves and an inclined waist. Concubine Qi used her looks and her trade to gain favor with the emperor, she would cry day and night pleading with him to install her son as the crown prince, Empress Lü united the important ministers in court against this notion but to no avail.

After the emperor died and Empress Lü came to power, she killed Concubine Qi’s son and did the following to Qi:

She cut off her arms and legs (Was it from the shoulders and the thighs so her entire arms and legs were gone?)

She plucked out her hair

Then deafened her ears with smoke (Did she pour sulphur or lead in her ears?)

Then gouged out her eyes

Then muted her with poison (Did she cut out her tongue too?)

Then she threw her in a lavatory (she lived for three more days, or was it thirty days?)

Then she brought her own son who had already been installed as Emperor Hui to see the ‘human pig’ and told him that this was Concubine Qi. Hui said that what his mother had done was inhuman and was so taken aback that he became ill and could no longer govern.

Despite the ‘human pig’ incident, Empress Lü governed for fifteen years, and was even recognized by the grand scribe Sima Qian as having the power of emperor, despite not having the title and he listed her in the Basic Annals of Records of the Grand Historian, which was reserved solely for Emperors. He even praised her as having the governance skills of the Yellow Emperor and Laozi, allowing the country to live in peace, and said that she “Without leaving the palace, reigned allowing China to be at peace, she used punishment with restraint, and criminals were rarely seen, people engaged in farming, with plenty to eat and with which to clothe themselves.” 122

The author character in the book then questions how much women have moved away from this paradigm of female jealousy, and ruminates on how much control the female characters who date Chen have in their relationships with him.

Although I found this novel by turns interesting, funny and disturbing, I didn’t really feel it came together as a gripping narrative and it was quite disjointed, although a coherent narrative may not have been the author’s goal. The characters lack the depth for the psychological elements of the book to have a real impact, but the serious topics skirted in the book make it hard to look at them as just satire. Although I wouldn’t go as far to say the book was written in expectation of analysis, it doesn’t go out of its way to give the reader a satisfactory experience and it was a frustrating read at times.

I’ve seen one Chinese-language review of the book too, which I’ve listed below:

林黛嫚 from 聯合報: http://mag.udn.com/mag/edu/storypage.jsp?f_ART_ID=521754