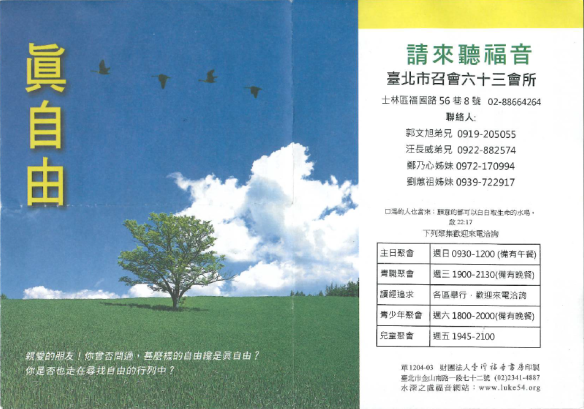

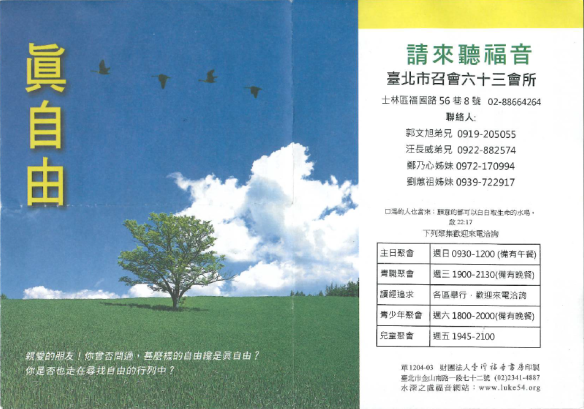

I got this leaflet through the letterbox the other night (the people called up to ask if they could put it inside) from a group called “The Church in Taipei”.

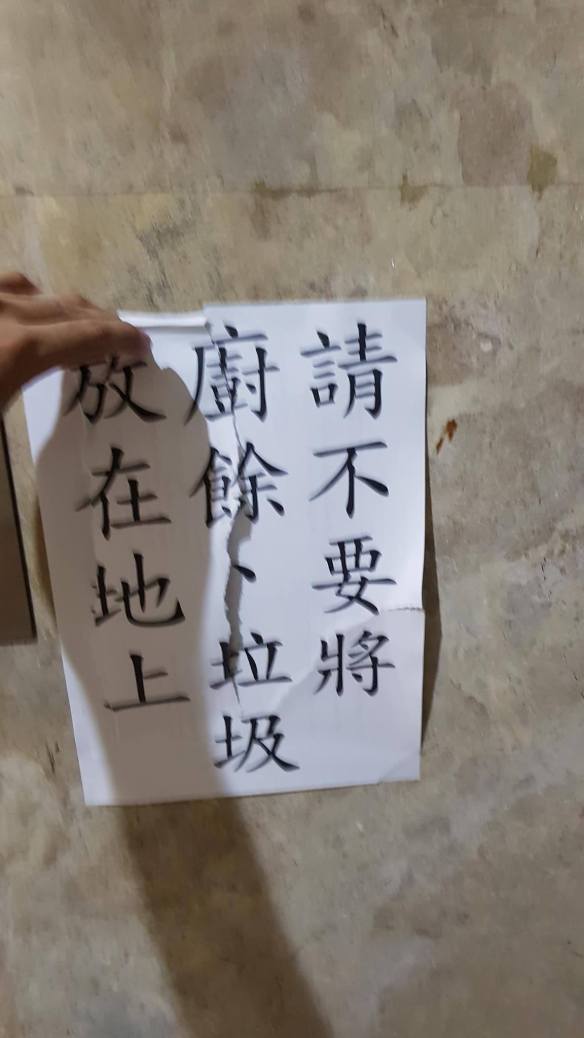

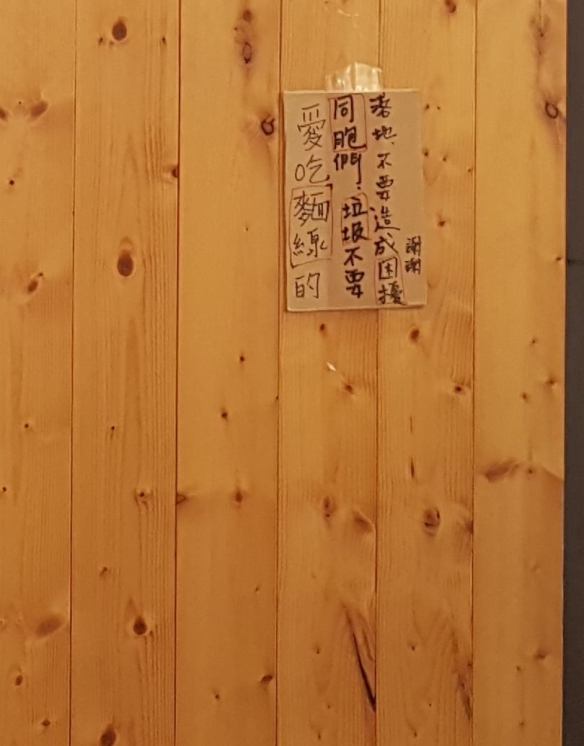

Leaflet from The Church in Taipei (highlights mine)

Although the content of the leaflet was largely unremarkable (we will help you find meaning for your life/true freedom), a few things about it did catch my eye.

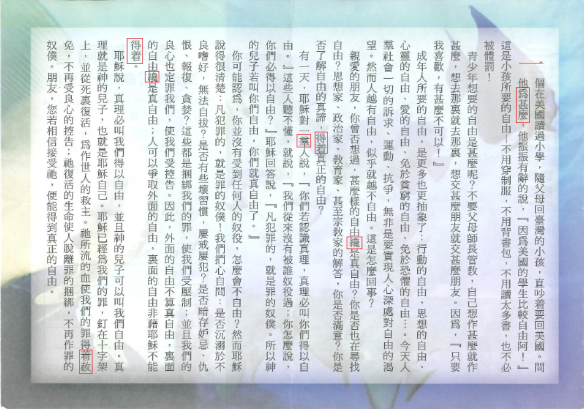

The first was a detail of the story:

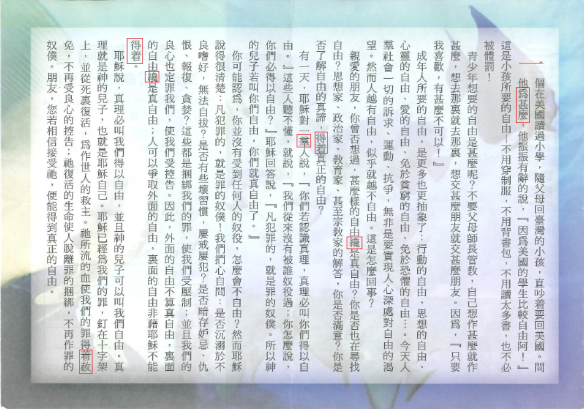

一個在美國讀過小學,隨父母回來臺灣的小孩,直吵着要回美國。問他爲甚麼,他振振有辭的說,『因爲美國的學生比較自由阿!』這是小孩所要的自由-不用穿制服,不用背書包,不用讀太多書,也不必被體罰!

A child who had gone to elementary school in the US and returned to Taiwan with their parents was going on and on asking to go back to the US. When you asked him why, he said precociously “Because American students have more freedom!”. This is freedom for a child – not having to wear a uniform, not having to carry a schoolbag, not having to read too many books and not having to undergo corporal punishment.

Leaving aside the suggestion that American kids don’t have to read or carry school bags, I thought it interesting that the author was unaware that corporal punishment is illegal in Taiwan.

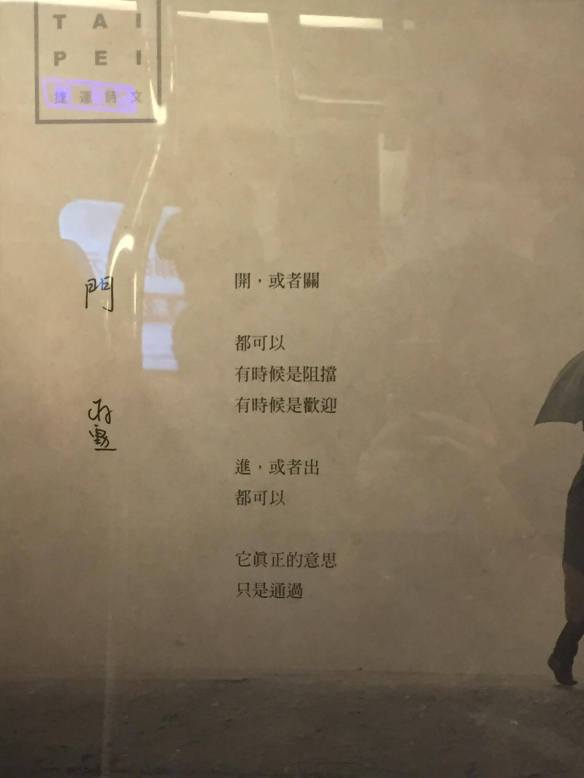

The other aspect of the leaflet that I found interesting was the choice of characters, which suggested the author wasn’t using the most common input system Zhuyin (Bopomofo), and that they were trying to some extent to sound authoritative through the use of more traditional variants. Some can be, perhaps, be ascribed to font choices, but I’m inclined to believe it is more of a stylistic choice. Examples are as below:

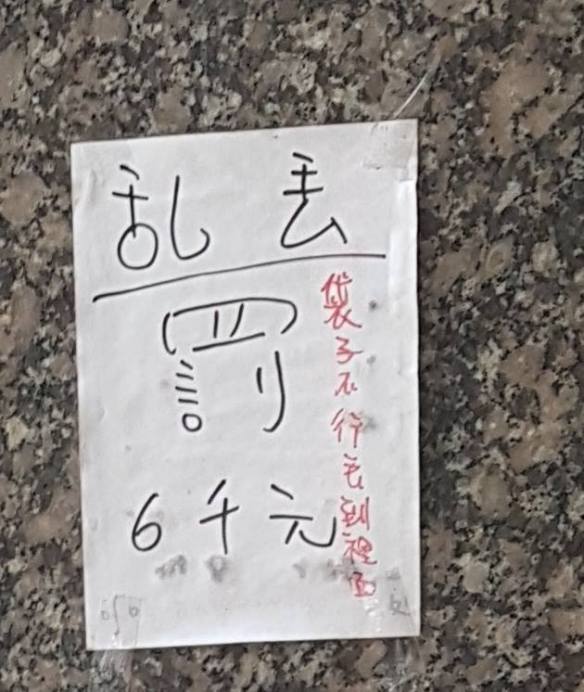

爲 vs 為

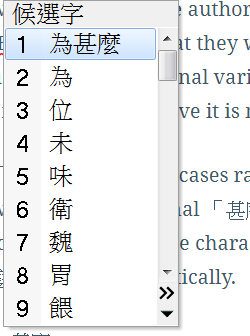

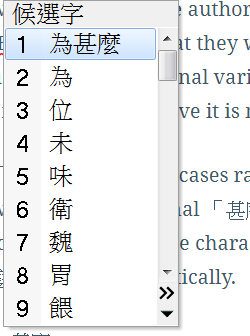

「爲」 is used in all cases in the leaflet above, rather than the more commonly seen 「為」, including together with the more formal 「甚麼」 in place of 「什麼」. If you’re typing in zhuyin you have to scroll to access the character 「爲」 whereas 為 will come out in combination with 什麼 and 甚麼 automatically:

Perhaps the author uses Cangjie or Sucheng, more popular input methods among older people in Taiwan.

着 vs 著

The character 「着」 is a variant of the character 「著」 and it’s also listed the standard simplified character, but it’s not often used in Taiwan:

纔 vs 才

I remember at university we had to learn to read texts in traditional Chinese. Many of the pre-Revolutionary texts from China used the traditional form 「纔 」 as opposed to 「才」 to mean “only then”. At several points in the text the author uses this more traditional form, however, both are listed in the Ministry of Education dictionary in separate listings, 「才」 has the additional meaning of talent or ability, but in this context they have similar meanings and 「才」is also the simplified version of 「纔」.

群 vs 羣

「羣」 is a variant of 「群」 and also suggests a stylistic choice made, rather than an accident.

This perhaps all makes sense when you think of the language used in the Bible in English and its surrounding literature, so this is perhaps an attempt to echo this kind of usage in Chinese.