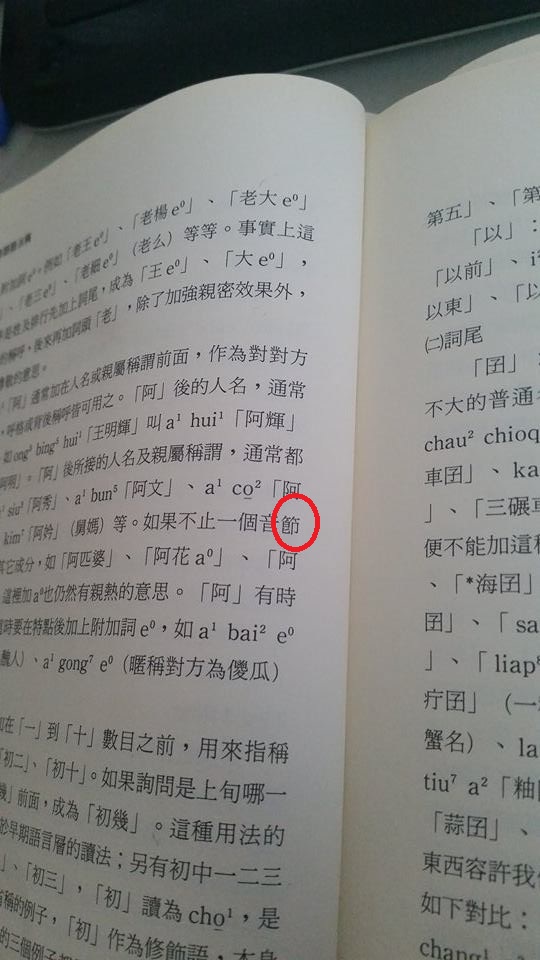

The character 「節」 can mean ‘festival’, ‘a joint or node’ or it can also mean ‘to use restraint’ or ‘to economize’. The Cangjie code when looking at the character is pretty straightforward: 「竹日戈中」. For those of those unfamiliar with Cangjie, you can find more info at the Cangjie input Wikipedia page. Basically for a character with three elements like 「節」 we break it into three constituent parts: 竹, the abbreviated form of 艮 and 卩. We take the 1st and last element of the first part – here that would be 竹 (which serves as both the first and the last element of the first part of the character), then the first and last element of the second part of the character which are 日 and 戈 (the dot on the bottom) and the last element of the final part of the character, which is 中 (a vertical line. This leaves us with 「竹日戈中」(hail) , however, when presented in certain fonts, like the one I found below, the appearance of the character in variant form, suggests alternative ways to write the character that do not work:

This rendering of the character 「![]() 」 suggests the Cangjie code 「竹竹心中」(竹 is the first and last element of the first part; 竹 (the top stroke of 白) and 心 (which is used to represent 匕) are the first and last elements of the second part and 中 is still the final element of the final part, however, this obviously doesn’t work, as the standard form is the one the code is based on. If anyone knows which font throws up this variant of 「節」 please let me know. You can find more variants of 節 at the Ministry of Education variant dictionary.

」 suggests the Cangjie code 「竹竹心中」(竹 is the first and last element of the first part; 竹 (the top stroke of 白) and 心 (which is used to represent 匕) are the first and last elements of the second part and 中 is still the final element of the final part, however, this obviously doesn’t work, as the standard form is the one the code is based on. If anyone knows which font throws up this variant of 「節」 please let me know. You can find more variants of 節 at the Ministry of Education variant dictionary.

Speaking of variant forms, after penning my last post on the variant forms of 「免」 I was amused to see the variant form 「![]() 」 used in a poster advertising the upcoming Taipei International Book Exhibition on the MRT:

」 used in a poster advertising the upcoming Taipei International Book Exhibition on the MRT:

Incidentally, the book exhibition is well worth a visit – it’s going to held from February 16-21 at the Taipei World Trade Center Exhibition Halls 1 and 3. It’s open 10am-6pm, with late night sessions until 10pm on Friday the 19th and Saturday the 20th, as well as until 8pm on Sunday the 21st. The first day at Exhibition Hall 1 is just for professionals, so you can visit from the 17th to the 21st, whereas Exhibition Hall 3 is open the whole time to everyone. It’s also free for under-18s.

Visit the MOE Variant Dictionary here.

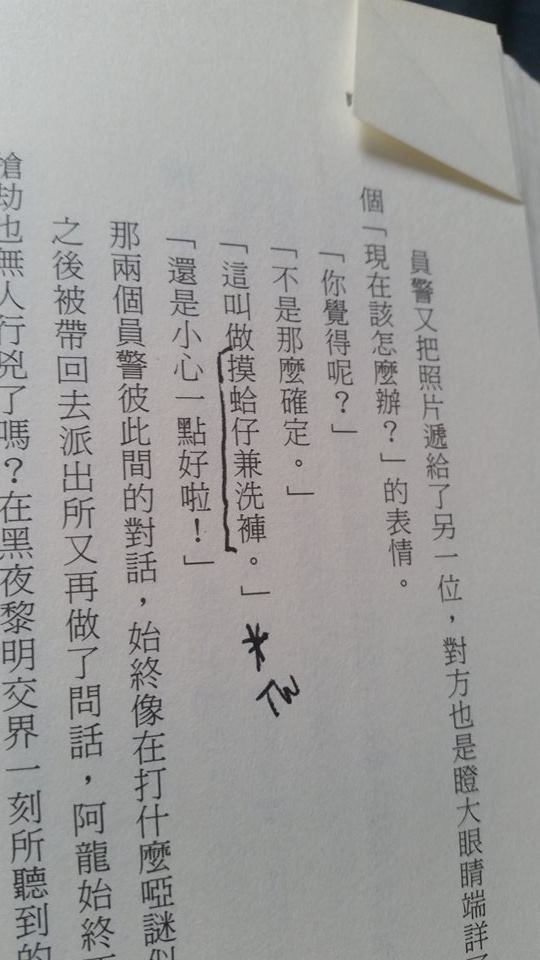

I found the Taiwanese equivalent for the phrase ‘catching two birds with one stone’ in the

I found the Taiwanese equivalent for the phrase ‘catching two birds with one stone’ in the

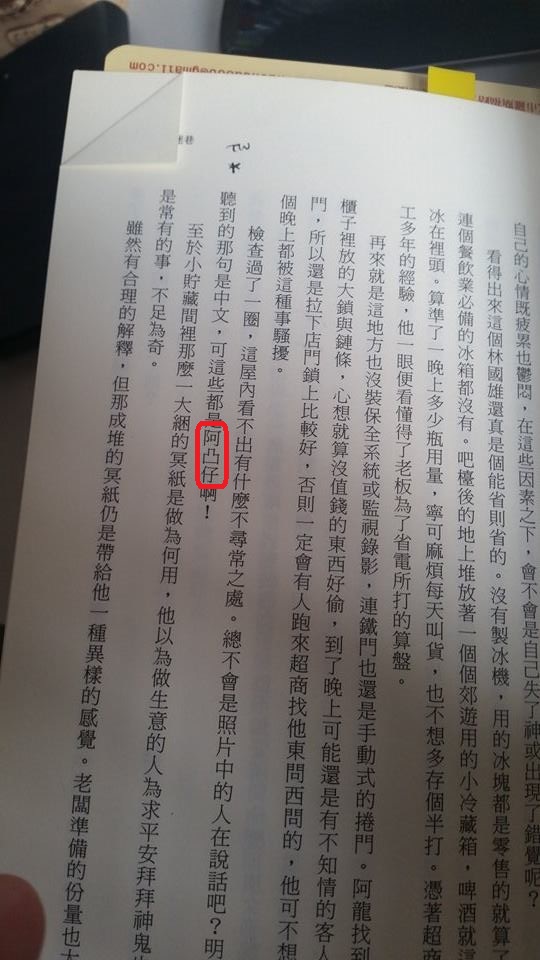

I came across the (somewhat controversial) Taiwanese phrase for (non-Asian) foreigner 「阿凸仔」 in a

I came across the (somewhat controversial) Taiwanese phrase for (non-Asian) foreigner 「阿凸仔」 in a

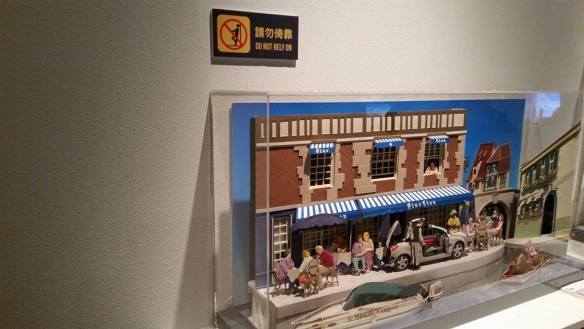

Although I’ve tired slightly of all but the most bizarre Chinglish signage, I thought this one was of note because it can be read as a covert injunction to aspiring paper artists everywhere – “Don’t rely on this kind of work, man.”

Although I’ve tired slightly of all but the most bizarre Chinglish signage, I thought this one was of note because it can be read as a covert injunction to aspiring paper artists everywhere – “Don’t rely on this kind of work, man.”