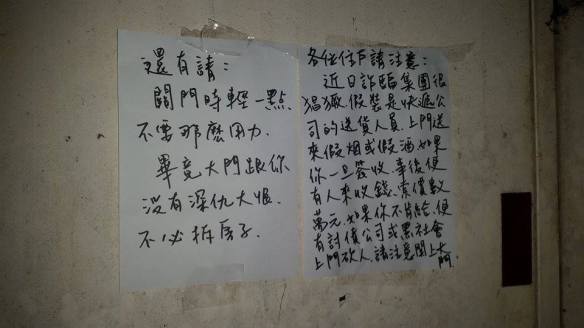

A lot of junk comes through my letterbox everyday. More often than not it’s housing advertisements, but I thought that this fortune telling class for local residents was quite interesting:

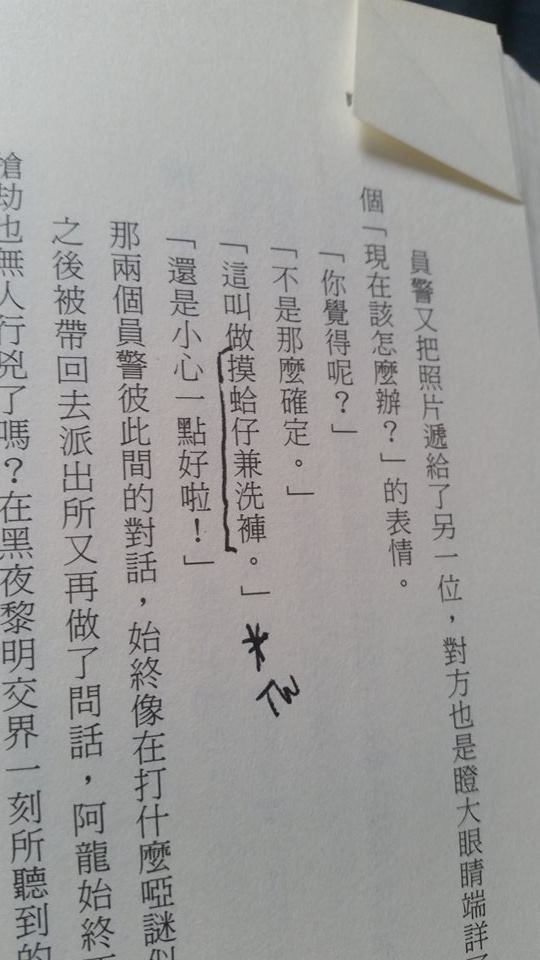

It reads:

REALLY ACCURATE!

A beginners’ class on the art of telling fortunes with people’s names

Do you want to know who is holding you back and who is there to help you? How much does one’s name influence one’s life?

In order to be of service to the residents of Wangxi Li, we’ve invited instructors from the Taiyi Numerology Centre to give classes to the residents of this li on the art of telling fortunes from names, so they can understand life and grow together!

The rest is details of the cost and contact information.

Many Taiwanese people that I have met are extremely superstitious, they believe in ghosts in a very literal way and they believe that if they’re having a run of bad luck they can change their luck in several ways. One of these ways is to change their name. Many Taiwanese people I know have changed their name at least once, some several times. Baby names in Taiwan are often chosen by fortune tellers and if you’ve been given a bad name, then you need to get it changed or you’ll be unable to turn your life around.

I’m not a massive fan of fortune telling and don’t hold any stock in it at all. Irish people have a lot of superstitions too, from older beliefs in leprechauns and fairies to the pseudo-Christian traditions of faith healers and relics (objects owned by saints or their body parts which are said to have magical healing powers). These traditions still go on today, for example, most irish cars will have holy water somewhere in them as a blessing. I also heard a story about a miraculous Medal being thrown into a house up for sale by interested buyers in the belief that it will secure them the property.

A good antidote to superstition like this is a play by Brian Friel called Faith Healer, although, obviously you’re free to believe what you want:

But the questionings, the questionings… They began modestly enough with the pompous struttings of a young man: Am I endowed with a unique and awesome gift? – my God, yes, I’m afraid so. And I suppose the other extreme was Am I a con man? – which of course was nonsense, I think. And between those absurd exaggerations the possibilities were legion. Was it all chance? – or skill? – or illusion? – or delusion? Precisely what power did I possess? Could I summon it? When and how? Was I its servant? Did it reside in my ability to invest someone with faith in me or did I evoke from him a healing faith in himself? Could my healing be effected without faith? But faith in what? – in me? in the possibility? – faith in faith? And is the power diminishing? You’re beginning to masquerade, aren’t you? You’re becoming a husk, aren’t you?

Faith Healer Brian Friel

I feel that some sociology doctoral candidate somewhere should take some of these classes though, as I find it so interesting how much this kind of thing affects people’s lives.

To be fair to the organizers, although the class costs NT$1000, those with low household incomes can take it for free.

I’ve heard lots of Taiwanese superstitions (/beliefs) over the years, like not whistling at night during Ghost Month; Oh yeah… Ghost Month, when the gates of hell open and ghosts come into the land of the living; Putting your umbrella down before you go inside (or a ghost will think you’re leading them in). And many more like this. How about you? Comment below with any beliefs that you’ve heard about in Taiwan.

I’m provided a link to the centre’s website (Chinese only) for anyone who is interested in the mechanics of how one’s fortune is told with one’s name. But this is not an endorsement.

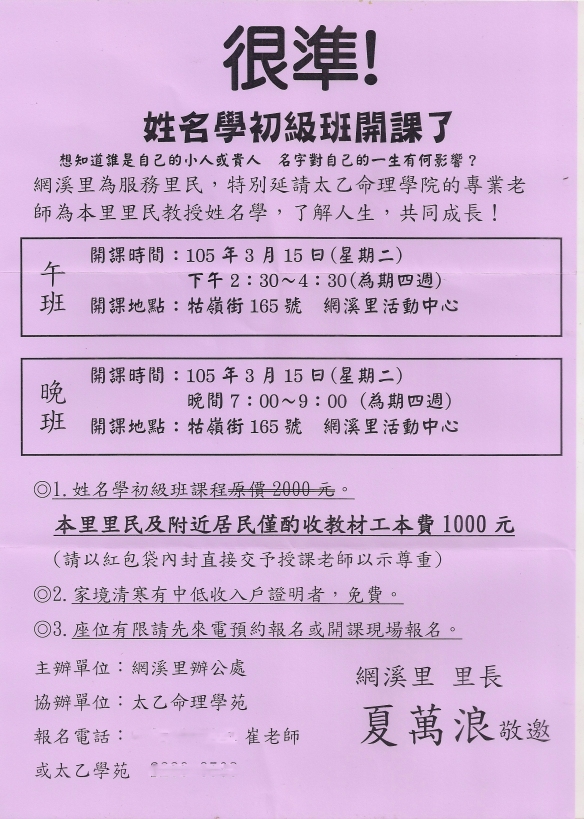

If you’ve been in Taiwan for a substantial period of time but didn’t grow up here, chances are you’ve sat on the outskirts of an hilarious conversation involving characters from the books of martial arts novelist Jin Yong (also known as Louis Cha) during which you’ve had completely no idea what was going on, or what the jokes were about. This has been my fate on several occasions, as, although I’ve bought several volumes of Jin Yong’s novels, I’ve never mustered up the courage to commit to reading a whole one and they’re currently rotting on my shelves. Given that generations of teenagers in Taiwan have read most of the Jin Yong canon, there are a lot of mainstream cultural references that revolve around these books.

If you’ve been in Taiwan for a substantial period of time but didn’t grow up here, chances are you’ve sat on the outskirts of an hilarious conversation involving characters from the books of martial arts novelist Jin Yong (also known as Louis Cha) during which you’ve had completely no idea what was going on, or what the jokes were about. This has been my fate on several occasions, as, although I’ve bought several volumes of Jin Yong’s novels, I’ve never mustered up the courage to commit to reading a whole one and they’re currently rotting on my shelves. Given that generations of teenagers in Taiwan have read most of the Jin Yong canon, there are a lot of mainstream cultural references that revolve around these books.

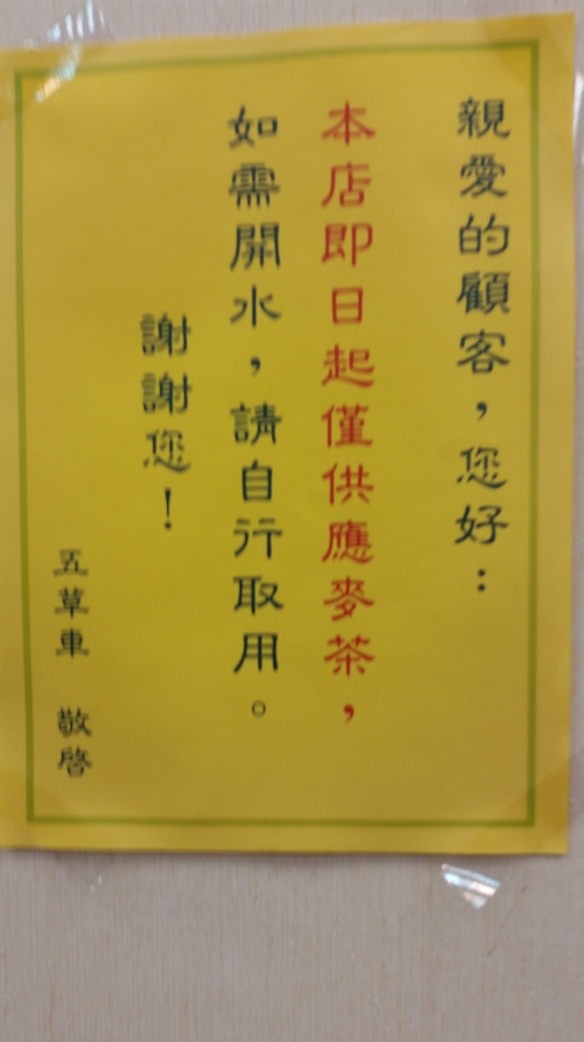

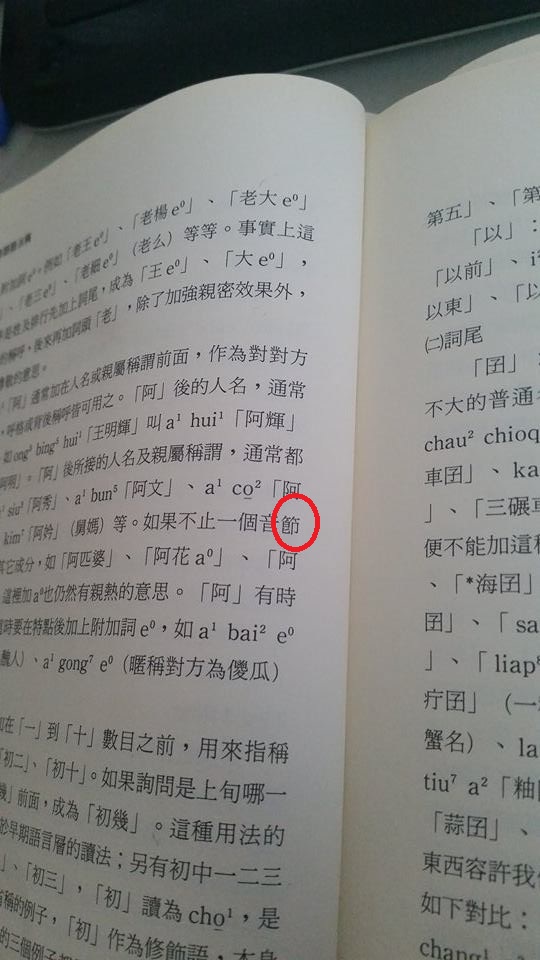

I found the Taiwanese equivalent for the phrase ‘catching two birds with one stone’ in the

I found the Taiwanese equivalent for the phrase ‘catching two birds with one stone’ in the