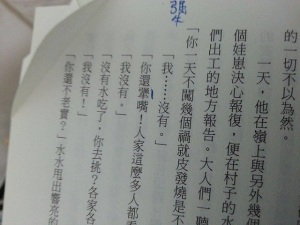

親愛的鄰居,

此處 禁止

蹓狗時,狗狗

在此隨地大便

~感謝您的留意~

Dear neighbours,

In this place it is forbidden

When walking a dog, for the dog

To shit anywhere here

~Thanks for your attention

The text I’ve marked in bold (thinner characters on the note in the photo) as if it was added on later, which suggests the person who wrote it was inadvertently accusing his or her neighbours of having a sneaky No. 2 in the alley while walking their dogs before realizing their mistake. They do not seem to have been arsed to redo the whole thing after putting a bit of effort into the ornate characters only to realize their mistake, which resulted in the sign being posted with rather odd grammatical structures. The “此處” (this place) makes the “在此” (here) a little unnecessary and the juxtaposition of “在此” (here) and “隨地” (anyplace/wherever one pleases) is a little odd too, as if the author thought that people might not realize that “anyplace” is inclusive of “here”.

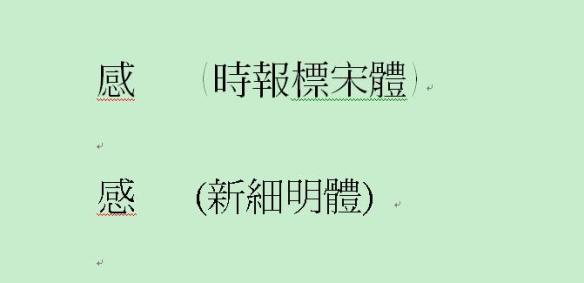

There’s also a pseudo-typo, in that 「遛狗」 is the more accepted way of saying “to walk a dog”, as opposed to the 「蹓狗」 written here. The character 「蹓」 comes from 「蹓躂」, a variant of 「遛達」 meaning to stroll, or to walk. Technically 「蹓」 can be seen as a variant, but doesn’t seem to be accepted as correct. When you type 「蹓狗」 into Google for example, you get the following prompt:

The search results that are currently displayed are from: 「遛狗」

You can change back to search for: 「蹓狗」

「遛狗」 fetches 1,060,000 results, whereas 「蹓狗」 only fetches 181,000, which suggests it’s not in standard use. I think these little idiosyncrasies are what make handwritten notes like this so interesting, as they inadvertently reveal certain characteristics of their authors.

After receiving some complaints about my previous post being more “openly aggressive” rather than “passive aggressive”, I think the 「新愛的 (scatological) 鄰居」 line makes this more of a passive aggressive post.

Let me know if you see any passive aggressive (or openly aggressive) notes in your area and feel free to submit anything you want featured!