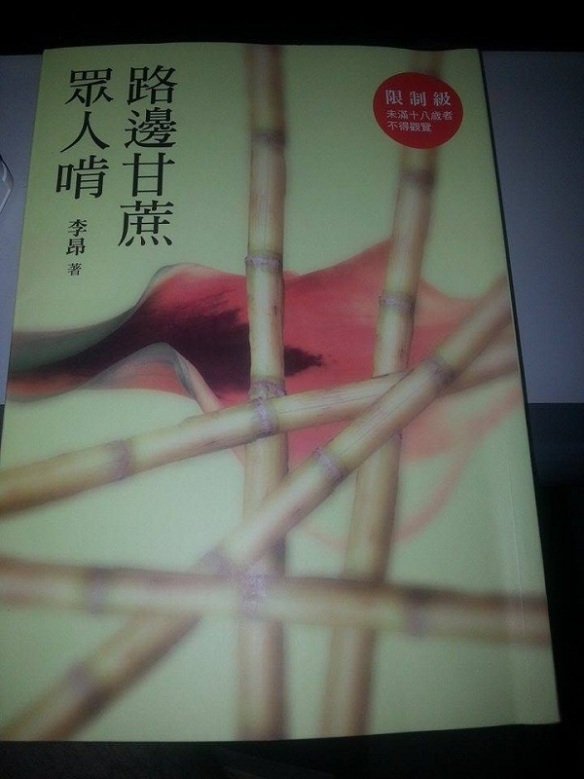

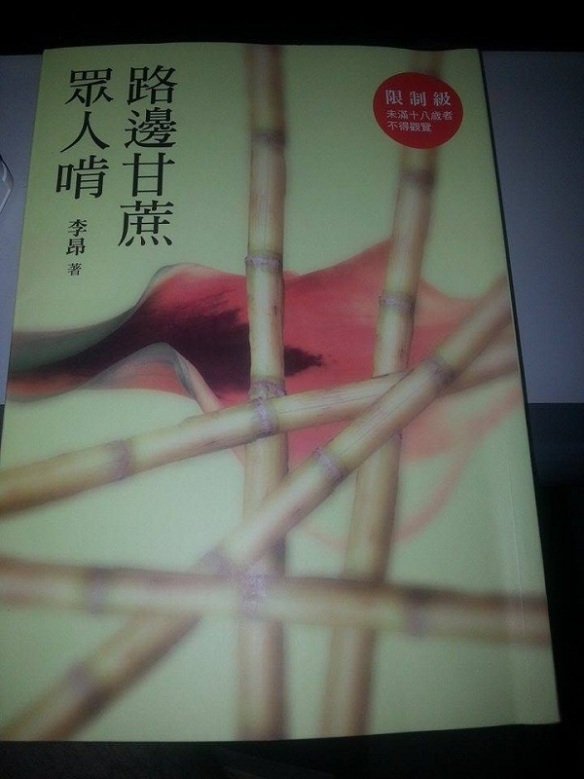

I have been jumping from book to book lately, so going to post what I’m reviewing next in the hope that this will put a little pressure on me to stick with one all the way through. I started I Am China by Xiaolu Guo, but not overly impressed by what I’ve read so far – a tired story about a Chinese dissident rocker who is seeking asylum in the UK that right now is seeming a little bit pretentious, somewhere between an Amy Tan novel and Ma Jian’s Red Dust, except not as edgy, equipped with dullish references to the Beat generation (((((Kerouac’s overrated))))) and China’s misty poets – but going to give it a chance, because I completely misjudged Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad and ended up loving it – so going to put it on the back-burner, and I am currently nose-deep in the long-awaited counterpart to Li Ang’s (李昂) 1997 work 《北港香爐人人插》 (Everyone sticks it in the Beigang incense burner) called 《路邊甘蔗眾人啃》 (Everybody nibbles on the sugar cane at the side of the road). The new book, published this year deals with men and power, whereas the previous book dealt with women and power. I haven’t read the previous book, but have heard interesting things about the author. I’m also interested to see if the “restricted to ages 18 and over” label stuck on the front is actually warranted, or is just a marketing technique.

The other books I’m lining up are 《馬橋詞典》 (A Dictionary of Maqiao in English) by Han Shaogong (韓少功), recommended to me by Chris Peacock, so looking forward to it.

I’m also going to give Yu Hua a second chance after the average but disappointing 《活著》 (To Live).

Got any recommendations? Reading any books that you are enjoying? Or read these books and want to have your say, comment below and I’ll get back to you.

Got any recommendations? Reading any books that you are enjoying? Or read these books and want to have your say, comment below and I’ll get back to you.

I’ve also got a review of A Touch of Sin by Jia Zhangke in the pipeline, it’s a great film.