I noticed a spike in views of one of my old posts, looking at the use of the term 「莊腳面」 in Wu Nien-chen’s Human Condition series of plays, which were the topic of my master’s thesis. When I googled the word again, the following news story from yesterday came up several times, suggesting it might be the reason people were looking for a definition of the term:

The article is entitled “Chang Jung-fa explains that even if you look like a bumpkin, you can still be a flight attendant” and seems to be largely a puff-piece. I just pictured a group of country bumpkins eager to become flight attendants eagerly googling what the term means.

Here’s the definition I previously posted:

莊腳面 chng-khabīn, basically means that someone’s face looks like they’re from the countryside, or a bumpkin. It’s not always used in the negative, as it can imply innocence or directness and honesty too, I guess it depends on what your opinion on people from the countryside is. I found an answer on Yahoo which gives quite a good explanation of 莊腳 and other terms, although I’m not sure if the first three are still used in Taiwanese:

莊頭 進入村莊前緣的地方 The beginning of the village

莊內 村莊中心的地方 The main part of the village

莊尾 村莊末端的地方 The tail end of the village

莊腳 chng-kha 村莊外圍偏遠的地方 The places on the outer margins of the village

(I know, inception-like quotations within quotations)So, this would make 莊腳 the bumpkin of bumpkins, as even the people in the village think he’s a bit rustic.

You probably noticed too, that the Chinese article I cited uses the character 「庄」, not the 「莊」 I used in my original post. 「庄」 is actually a variant of 「莊」(village) according to the Ministry of Education Dictionary. I thought this was interesting, as I think that CNA used the variant in order to be sure people knew to read it as Taiwanese. As with most of my theories, I’ve got little proof, but would be eager to find out if anyone knows of similar examples.

It’s relatively unusual for newspapers not to put the Chinese translation in brackets after a Taiwanese phrase is used unless it’s extremely common, which might explain why so many people were Googling the word. If you’re Taiwanese you can comment on how common this word is. On the other hand it could just have been lots of foreigners who came across the Chinese article and didn’t know what it meant.

Feel free to comment below or message me with any strange or startling Taiwanese phrases you come across or even with sketches the typical 「莊腳面」.

I found the Taiwanese equivalent for the phrase ‘catching two birds with one stone’ in the

I found the Taiwanese equivalent for the phrase ‘catching two birds with one stone’ in the

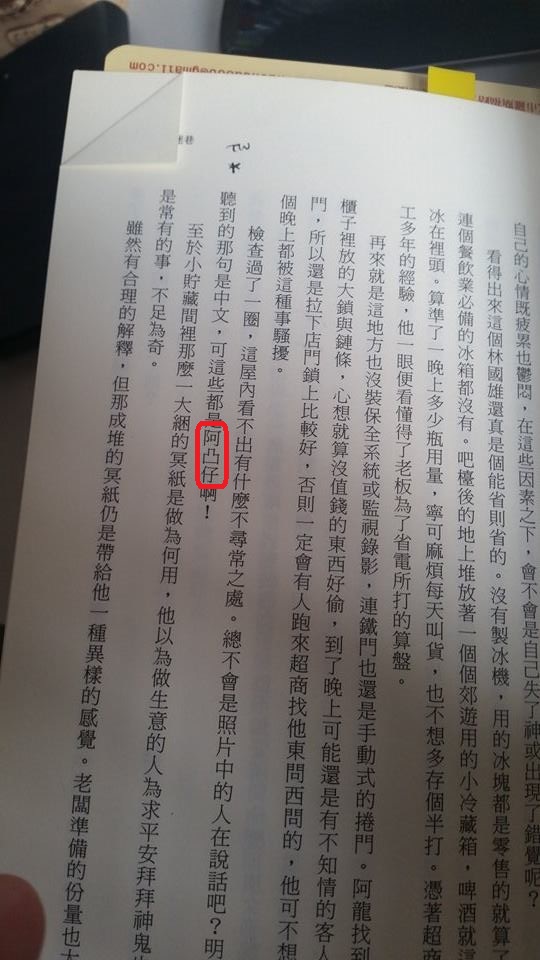

I came across the (somewhat controversial) Taiwanese phrase for (non-Asian) foreigner 「阿凸仔」 in a

I came across the (somewhat controversial) Taiwanese phrase for (non-Asian) foreigner 「阿凸仔」 in a

A錢

A錢