When I was still a student at the Graduate Institute of Taiwan Literature, an American professor came to visit one of my professors and, as one of the two resident foreigners in the department, I was enlisted to see what it was he wanted over dinner. The professor was Maurice A. Lee (see picture second left) and he was hoping to organize a conference in Taiwan, unfortunately our research institute didn’t have the funds to make it happen, but we had a nice chat.

Some years later, Taiwanese author Wu I-Wei (吳億偉) asked me to translate a short story for him called ‘The Face Changer’ (〈換照者〉), which it turns out has been published in a new anthology edited by Maurice A. Lee called Unbraiding the Short Story, which includes short stories from all around the world. Looks like an interesting read, here’s a quick sample of Wu’s story:

The face changer had been born without a face. His mother said that he’d wanted it that way. Back when he was in his mother’s womb, she was unable to make him whole, and he had to face the world lacking. The only favor his mother granted him was helping him decide which part of his body to go without. Floating in his mother’s amniotic fluids like a corpse, he saw his arms, his two feet, and his body, he felt reluctant to part with the bits he’d already seen, but that only left his face, the only thing he couldn’t see, after his tacit response to his mother’s question, he cried out, and then came into the world.

He scared the doctors and nurses in the room when he was born, each of them guessing as to what the child would look like when he grew up. This would be the reason that he would later change his face so much, but it wasn’t because he wanted to shock everyone, with a face that could never be pinned down, but rather that he wanted all their guesses to come true, to satisfy all of their imaginings. Before his face-changing days, back when he was young, he faced a lot of challenges. His mother was worried that he’d scare people, so she drew a face for him. Lacking in imagination as she was, however, the eyes, nose and mouth she drew were those from your average picture book, his features all curved in shape, with eyes like rainbows, and a mouth like an upturned rainbow. If his mother had remembered, she would have drawn a little dot for his nose too.

What a splendid face she had drawn him, it always looked so happy that whenever his teacher saw him, she would pinch his cheeks, asking him why he smiled all day long. He couldn’t open his mouth to say anything, so he could only smile in response. As his expression was dictated beforehand, he became the nice guy in his class, and gave the impression of having a particularly good temper. If people hit or cursed at him, he’d still smile away. Sometimes a teacher would intervene, then seeing that the look on his face hadn’t changed a fraction, they would say how innocent he seemed, like an angel…

換照者一生下來就沒有臉。他母親說這是他自己要求的,早在娘胎的時候他母親便無力給他一個完整的身體,他得缺陷的面對這個世界,他母親唯一能幫忙的,就是讓他決定要缺少哪個部份,像個浮屍般漂在母親羊水中的他,看到自己的雙手,看到自己的雙腳,看到自己的身體,這些看得到的他都不想放手,只剩下臉了,他唯一看不到的東西,悄悄回答母親的問題後,哇的一聲,就見到這個世界了。

據說剛出生的時候他嚇到在場的醫生護士,大家紛紛猜測這小孩長大之後會長怎樣,這可以說是他日後之所以換照的遠因,但絕對不是因為他想要跌破大家眼鏡,擁有一張他們猜不到的臉,而是他要大家的猜測紛紛成真,滿足每一個人的想像。在這之前他年幼當然也受到了一些挑戰,他母親怕他嚇到大家,幫他畫上了一張臉,只能怪他母親想像力貧瘠,他的眼睛鼻子嘴巴就是那種在一般畫冊中看到的,臉上五官都由弧線所構成,眼睛像彩虹,而嘴巴則是反過來的彩虹,若是他母親記得的話,會在彩虹的中間補上一點,那是鼻子。多麼燦爛的臉啊,看起來永遠那麼快樂,學校老師看到他,總喜歡捏捏他的臉,摸摸他的眼睛,嘴巴,你怎麼一天到晚都在笑,他沒有辦法張口說話,只能微笑以對。由於他的表情使然,成為班上有名的好好先生,沒有脾氣,不管別人怎麼罵他打他,還是笑容滿溢,老師幾次幫他解圍,看到他表情沒有一絲一毫的改變,直呼他真是天真,如天使般……

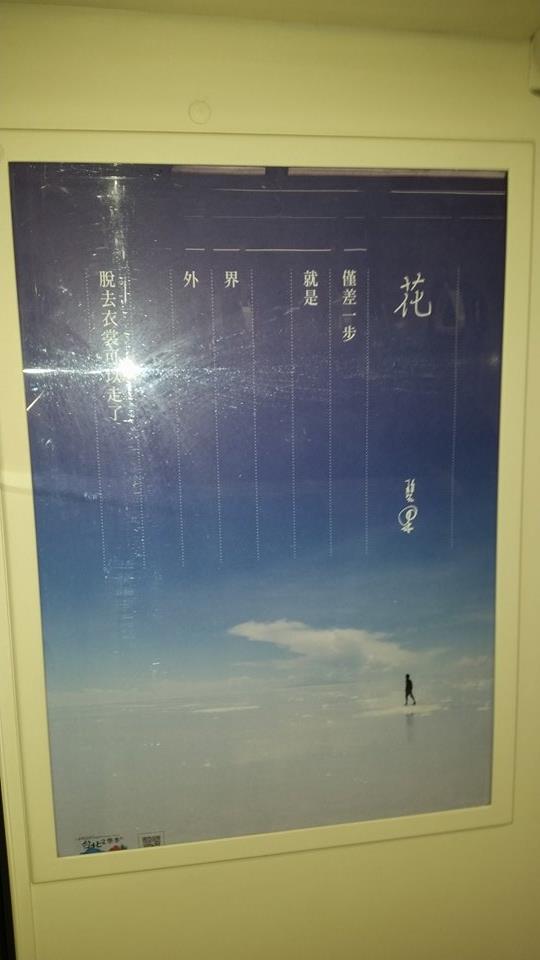

Wu has won numerous awards including the United Daily Press Literary Award for Fiction, the China Times Literary Award for Fiction and Essays, the United Literature Monthly Literary Award for Fiction, and the Liberty Times Lin Rungsan Literary Award for Short Essays. He published his new collection of essays, Motorbike Days (《機車生活》), in 2014 and is now a PhD candidate at the Institute of Chinese Studies at the University of Heidelberg in Germany and regularly reports the latest German literature news for Taiwanese magazines and newspapers.

Still working on reviews, not given up on the blog, expect more content soon.

I came across the (somewhat controversial) Taiwanese phrase for (non-Asian) foreigner 「阿凸仔」 in a

I came across the (somewhat controversial) Taiwanese phrase for (non-Asian) foreigner 「阿凸仔」 in a

A錢

A錢